Gases are unlike other states of matter in that a gas expands to fill the shape and volume of its container. For this reason, gases can also be compressed so that a relatively large amount of gas can be forced into a small container.

Q. What is the repulsive force?

Definitions of repulsive force. the force by which bodies repel one another. synonyms: repulsion. Antonyms: attraction, attractive force. the force by which one object attracts another.

Table of Contents

- Q. What is the repulsive force?

- Q. What is non ideal gas?

- Q. Do gas molecules repel each other?

- Q. Do gas molecules stop moving?

- Q. What is the real gas equation?

- Q. What is the real gas example?

- Q. What is real gas and ideal gas?

- Q. How do you find real gas pressure?

- Q. What is a real gas Class 11?

- Q. What is ideal gas behavior?

- Q. What is Vander Waals equation for real gas?

- Q. What is pressure of real gas?

- Q. What are Vander Waals constants?

- Q. What is Boyle point of a gas?

- Q. Why do real gases deviate from ideality?

- Q. What is critical point for a real gas?

- Q. What is needed for a pressure to be exerted by a gas?

- Q. What causes gas exert pressure when confined in a container?

- Q. Why is pressure equal in all directions?

Q. What is non ideal gas?

As mentioned in the previous modules of this chapter, however, the behavior of a gas is often non-ideal, meaning that the observed relationships between its pressure, volume, and temperature are not accurately described by the gas laws.

Q. Do gas molecules repel each other?

The gas particles neither attract or repel one another (they possess no potential energy). The motion of the gas particles is completely random, so that statistically all directions are equally likely.

Q. Do gas molecules stop moving?

According to the physical meaning of temperature, the temperature of a gas is determined by the chaotic movement of its particles – the colder the gas, the slower the particles. At zero kelvin (minus 273 degrees Celsius) the particles stop moving and all disorder disappears.

Q. What is the real gas equation?

The difference below shows the properties of real gas and ideal gas, and also the ideal and real gas behaviour….Ideal and Real Gases.

| Ideal Gas | Real Gas |

|---|---|

| Obeys PV = nRT | Obeys p + ((n2a )/V2) (V – nb ) = nRT |

Q. What is the real gas example?

Any gas that exists is a real gas. Nitrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, helium etc. Real gases have small attractive and repulsive forces between particles and ideal gases do not. Real gas particles have a volume and ideal gas particles do not.

Q. What is real gas and ideal gas?

A real gas is a gas that does not behave according to the assumptions of the kinetic-molecular theory. In summary, a real gas deviates most from an ideal gas at low temperatures and high pressures. Gases are most ideal at high temperature and low pressure.

Q. How do you find real gas pressure?

For real gases, we make two changes by adding a constant to the pressure term (P) and subtracting a different constant from the volume term (V). The new equation looks like this: (P + an2)(V-nb) = nRT.

Q. What is a real gas Class 11?

A gas which obeys the ideal gas equation, PV =nRT under all conditions of temperature and pressure is called an ideal gas. Such gases are known as real gases. It is found that gases which are soluble in water or are easily liquefiable show larger deviation than gases like H2, O2, N2 etc.

Q. What is ideal gas behavior?

For a gas to be “ideal” there are four governing assumptions: The gas particles have negligible volume. The gas particles are equally sized and do not have intermolecular forces (attraction or repulsion) with other gas particles. The gas particles move randomly in agreement with Newton’s Laws of Motion.

Q. What is Vander Waals equation for real gas?

For real gases the relation between p, V and T is given by van der Waals equation: (p+V2an2)(V−nb)=nRT. where ‘a’ and ‘b’ are van der Waals constants, ‘nb’ is approximately equal to the total volume of the molecules of a gas.

Q. What is pressure of real gas?

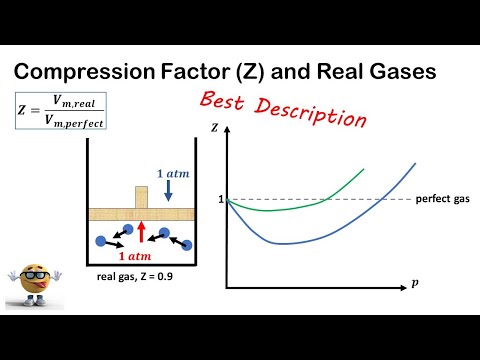

For a given pressure, the real gas will end up taking up a greater volume than predicted by the ideal gas law since we also have to take into account the additional volume of the gas molecules themselves. This increases our molar volume relative to an ideal gas, which results in a value of Z that is greater than 1.

Q. What are Vander Waals constants?

The constants a and b are called van der Waals constants. They have positive values and are characteristic of the individual gas. If a gas behaves ideally, both a and b are zero, and van der Waals equations approaches the ideal gas law PV=nRT. The constant a provides a correction for the intermolecular forces.

Q. What is Boyle point of a gas?

Boyle’s temperature or Boyle point is the temperature at which a real gas starts behaving like an ideal gas over a particular range of pressure. A graph is plotted between the compressibility factor Z and pressure P.

Q. Why do real gases deviate from ideality?

Gases deviate from the ideal gas behaviour because their molecules have forces of attraction between them. At high pressure the molecules of gases are very close to each other so the molecular interactions start operating and these molecules do not strike the walls of the container with full impact.

Q. What is critical point for a real gas?

The critical point is the temperature and pressure at which the distinction between liquid and gas can no longer be made.

Q. What is needed for a pressure to be exerted by a gas?

Pressure within a gas depends on the temperature of the gas, the mass of a single molecule of the gas, the acceleration due to gravity, and the height (or depth) within the gas.

Q. What causes gas exert pressure when confined in a container?

Gas pressure is caused by the collisions of the gas particles with the inside of the container as they collide with and exert a force on the container walls. This means that the particles hit off the sides more often and with greater force. Both of these factors cause the pressure of the gas to increase.

Q. Why is pressure equal in all directions?

Pressure at any point below the upper boundary of fluids, such as air and water, is uniform in all directions due to the fluid molecules being in constant motion and continually bumping into one another.